In a historic move that has since been controversial, the Bank of England (BoE) sold roughly half of its gold reserves in 1999 at the price bottom of the world’s leading commodity. This move resulted in a financial long-term opportunity cost of over £21 billion to BoE.

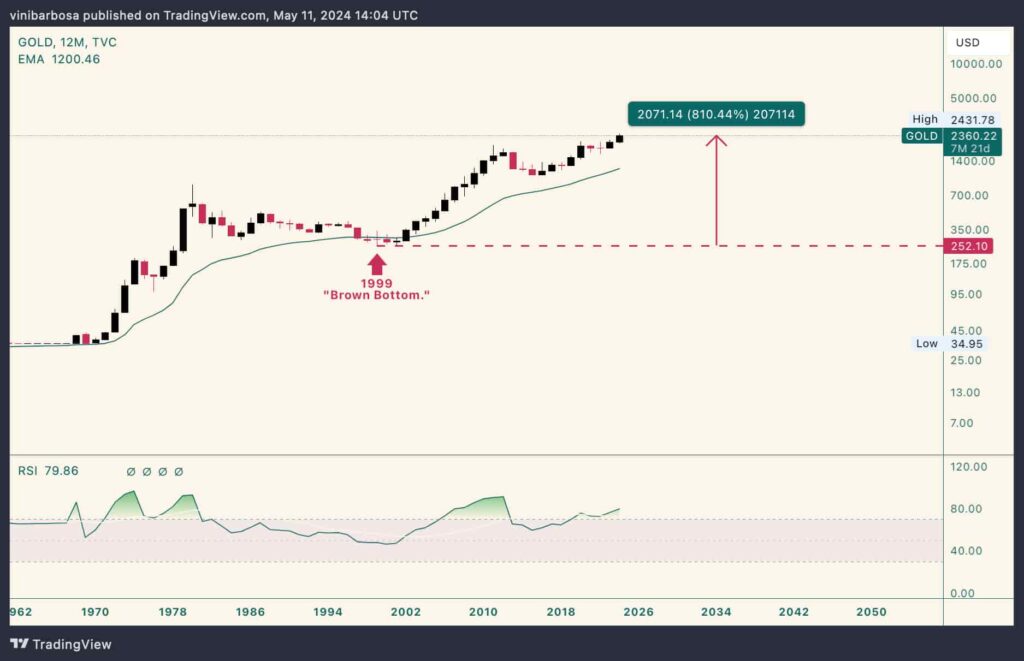

Notably, the then-Chancellor of the Exchequer, Gordon Brown, decided to sell 395 tonnes of gold, raising $3.5 billion. The sale drove gold prices to a historic low of $252.80 an ounce, which has since been referred to as the “Brown Bottom.”

As of this writing, gold trades at $2,360 per ounce—810% more than at the “Brown Bottom.”

According to a recent analysis by the Conservative Party, the value of the gold sold by Labour would have been worth £23.6 billion today. This means that the decision has cost the U.K. £21.3 billion more than what the Treasury received in 1999. Gold traders questioned the timing of the sale, noting that the price was near its lowest at the time.

Britain’s gold sale in 1999 amid an ‘expanding economy’

In particular, the BoE’s decision was part of a broader trend among central banks in the mid-1990s and early 2000s. Other countries, such as Canada, Argentina, the Netherlands, Austria, and France, also sold gold during this period. Interestingly, the sales were driven by the belief that gold was an outdated relic and that the global economy was expanding.

However, the sales led to growing concern that uncoordinated central bank gold sales were destabilizing the market. In response, central banks agreed to limit their gold sell-offs through the Central Bank Gold Agreement, also known as the Washington Agreement on Gold. The agreement was renewed every five years until its expiration in September 2019.

Gold demand has increased over the years

Fast forward to today, and the global fiscal picture has completely changed. Central banks have steadily accumulated gold for the last 12 years, buying more than 2,000 tonnes in the last two years alone. In the first quarter of 2024, central banks bought 290 tonnes of gold, the strongest start to a year on record.

Central banks are shifting toward gold to improve the quality of their reserves, holding a neutral asset. Emerging market central banks have been the dominant players in official sector gold demand. This is because these markets need to diversify their holdings away from U.S. dollar-denominated debt.

For example, China’s demand for gold surged 68% year-over-year in the first quarter of 2024. The increase happens as veteran investors warn of an incoming global crash.

While some analysts expect developed market central banks to start buying gold, others believe that gold faces an institutional problem. Essentially, most central bank economists still view gold as an outdated relic. Therefore, it will take a massive shift in thinking to change this view.

In conclusion, the BoE’s decision to sell half its gold reserves in 1999 has been costly for the U.K. The sale drove gold prices to historic lows and cost the country £21.3 billion more than the Treasury received. While the decision was part of a broader trend among central banks then, the global fiscal picture has since changed, with central banks now accumulating gold at a record pace.