Summary

⚈ Building and upgrading Alcatraz cost the equivalent of over $33 million in today’s dollars.

⚈ The proposal aligns with Trump’s tough-on-crime agenda.

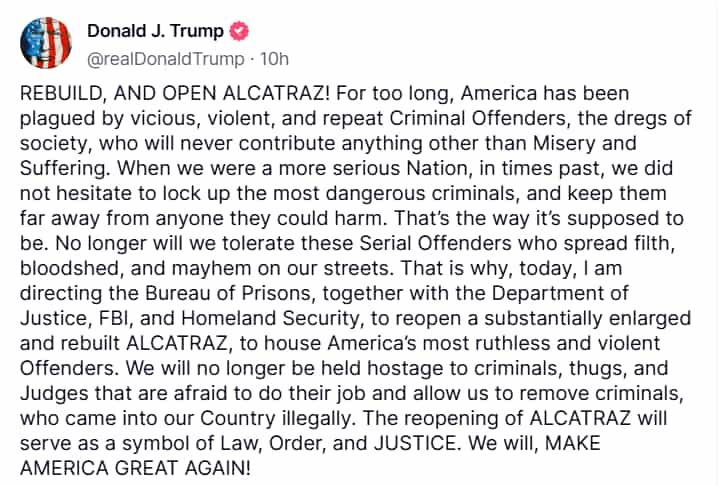

Alcatraz, the infamous island prison once known for housing America’s most dangerous criminals, is back in the spotlight after President Donald Trump announced plans to rebuild and reopen it. In a post on his Truth Social platform, Trump said he was directing federal agencies to restore and expand the long-shuttered facility to house the country’s “most ruthless and violent offenders,” calling it a “symbol of law, order and justice”.

The proposal has sparked intense debate. Once the most expensive federal prison to operate, Alcatraz was closed in 1963 due to crumbling infrastructure and high maintenance costs. Today, it’s a major tourist destination (attracting 1.5 million visitors each year) and a protected national historic landmark, raising questions about the practicality, legality, and cost of bringing back one of America’s most ruthless prisons.

How much would building Alcatraz prison cost today?

The main concrete cellhouse at Alcatrez, considered the longest of its kind in the world at the time, was built between 1910 and 1912 at a cost of $250,000, which amounts to roughly $8 million today.

But the spending didn’t stop there. Between 1934 and 1941, additional upgrades and security overhauls, including reinforced cells, electric locking systems, and new guard towers, brought total redevelopment costs into the millions. One major upgrade in 1939–1940 alone cost $1.1 million (around $25 million in today’s dollars) as the prison prepared to operate at peak wartime capacity.

Conditions at Alcatraz

Though Alcatraz had a fearsome reputation, the reality of life on the island was more complex. Known for housing the most disruptive and escape-prone inmates in the federal system, it was designed to be tough, but not necessarily brutal.

Prisoners followed a strict daily routine, lived in small individual cells, and were heavily monitored. Early on, rules were harsh, with strict silence enforced and minimal privileges. Still, some inmates actually requested to be transferred to Alcatraz, reporting better food, safer conditions, and a sense of order compared to other prisons.

Over time, restrictions eased. By the 1950s, prisoners were allowed to read books from a well-stocked library, play musical instruments (Al Capone famously practiced banjo in the showers) and watch movies on weekends. Those who earned privileges could work jobs in the laundry, the tailor shop, or the gardens.

What truly set Alcatraz apart, however, was its security. Located on a rocky island surrounded by freezing, current-filled ocean water, it was considered escape-proof. In its 29 years of operation, 36 men attempted to escape. Most were caught, a few were killed, and five disappeared without a trace, presumed drowned. None were ever confirmed to have made it off the island alive.

Outsourcing justice

Trump’s push to reopen Alcatraz comes amid ongoing clashes between his administration and the courts over his hardline approach to criminal justice. He has invoked an 18th-century law to deport accused gang members without due process and has even floated the idea of sending U.S. citizens convicted of violent crimes to El Salvador’s controversial maximum-security facility, the Terrorism Confinement Center, known as CECOT.

CECOT has become the centerpiece of El Salvador’s sweeping anti-gang crackdown. “It’s like Guantánamo on steroids,” said Juan Pappier of Human Rights Watch. Built under a state of exception that suspended constitutional rights, the prison holds thousands of people, many arrested without due process.

The prison currently holds 15,000 inmates, with a capacity for up to 40,000. Conditions are harsh: up to 80 men share a cell with no mattresses, limited water, and bright lights that never turn off, except in pitch-dark solitary confinement. Inmates get just 30 minutes of exercise daily in a caged yard with no sunlight, no visitors, and no contact with the outside world. Only one man is known to have left the prison alive, and he was quietly transferred elsewhere.

Officially, CECOT isn’t designed for rehabilitation; it’s built for long-term punishment and isolation, a place so brutal that a Salvadorian justice minister once said the “only way out is in a coffin”. And while popular in El Salvador for cutting gang violence, critics say the model is unimaginably cruel, and dangerously appealing to tough-on-crime leaders like Trump.

Featured image via Shutterstock.