If you’ve ever wondered why people poured so much money into websites that delivered dog food or how an online toy store became Wall Street’s darling, you’re in the right place. This guide will dissect the dot-com bubble in all its glory. We’ll delve deep into the factors that led up to this digital frenzy, the profound effects it had on the economy and investors, and the indelible legacy it left behind.

Best Crypto Exchange for Intermediate Traders and Investors

-

Invest in cryptocurrencies and 3,000+ other assets including stocks and precious metals.

-

0% commission on stocks - buy in bulk or just a fraction from as little as $10. Other fees apply. For more information, visit etoro.com/trading/fees.

-

Copy top-performing traders in real time, automatically.

-

eToro USA is registered with FINRA for securities trading.

Summary

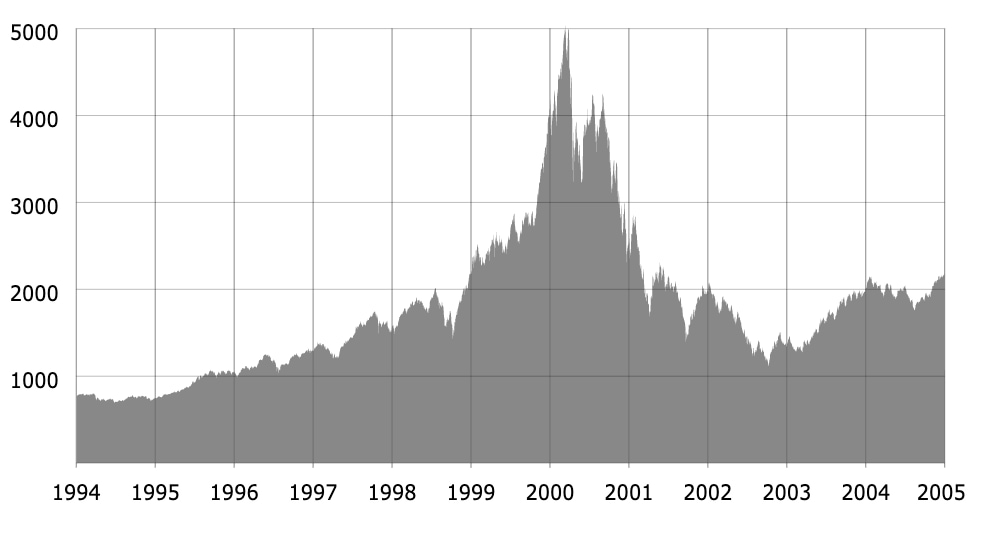

– Definition: The dot-com bubble (1995–2000) was a period of excessive speculation in internet-based companies, leading to inflated stock prices;

– Rapid growth: The Nasdaq Composite index surged five-fold during this time;

– Burst and aftermath: In 2000, the bubble burst, causing the Nasdaq to plummet by 76.81% by October 2002, resulting in numerous dot-com bankruptcies and significant investor losses;

– Long-term market impact: It took 15 years for the Nasdaq to regain its March 2000 peak, highlighting the enduring effects of the crash on the stock market.

The dot-com bubble definition

Unfortunately, things started to change in the late 2000s once investors realized many of these companies had business models that weren’t viable, ushering in a bear market that would last around two years and affect the entire stock market.

The crash saw the Nasdaq index plunge 76.81%, from a peak of 5,048.62 on March 10, 2000, to 1,139.90 on October 4, 2002, culminating in the majority of dot-com stocks going bust and evaporating trillions of dollars of investment capital in its wake. It would take 15 years for the Nasdaq to retrieve its peak, which it did on April 24, 2015.

Recommended video: The dot-com bubble explained in 3 minutes

Beginner’s corner:

- What is Investing? Putting Money to Work

- 17 Common Investing Mistakes to Avoid

- 15 Top-Rated Investment Books of All Time

- How to Buy Stocks? Complete Beginner’s Guide

- 10 Best Stock Trading Books for Beginners

- 15 Highest-Rated Crypto Books for Beginners

- 6 Basic Rules of Investing

- Dividend Investing for Beginners

- Top 6 Real Estate Investing Books for Beginners

- 5 Passive Income Investment Ideas

What are asset bubbles?

The dot-com bubble is an example of an asset bubble, sometimes referred to as a financial, economic, or speculative bubble. Noteworthy examples from history include the stock market bubble of the 1920s that led up to the Great Depression and the real estate bubble of the 2000s that culminated in the Great Recession.

An asset bubble occurs when an asset’s price rises rapidly over a short period and trades much higher than its fundamentals suggest. Asset bubbles are fueled by increased money supply and particular historical circumstances (e.g., rapid technological expansion). The hallmark of a bubble is irrational exuberance*— the unfounded economic optimism that sees investors flock around a particular asset class without good reason.

During a bubble, investors bid up the price of an asset beyond its intrinsic value. Like a snowball, the bubble feeds on itself. The higher the prices, the more opportunistic investors jump in—the expectation of future price appreciation inviting in additional dollars, inflating the price even further.

Eventually, once prices crash and demand falls, the bubble pops, wreaking havoc for latecomers to the game, most of whom lose a large percentage of their investments. The burst has dire outcomes, such as reduced business and household spending and a potential economic decline (recession).

*The term irrational exuberance was coined in December 1996 by Federal Reserve Board chairman Alan Greenspan and widely interpreted as a warning that the stock market might be overvalued.

Recommended video: What causes economic bubbles?

The dot-com bubble explained

The 90s witnessed rapid technological progress in many areas across the U.S. However, the commercialization of the Internet led to the most remarkable expansion of capital growth in the country ever, seeing many investors eager to invest, at any valuation, in any dot-com company, especially if it had a “.com” after its name.

Ultimately, this grew into what’s now known as the dot-com bubble (aka dot-com boom, tech bubble, Internet bubble), triggered by a combination of speculative investing, market overconfidence, a surplus of venture capital funding, and the failure of Internet startups to turn a profit. It saw both venture capitalists and individual investors pour money into Internet-based companies, hoping they would one day become profitable, abandoning all caution for an opportunity to capitalize on the growing dot-com novelty vision.

Many investors expected Internet-based companies to succeed merely because the Internet was an innovation, even though the price of tech stocks soared far past their intrinsic value, increasing much faster than their counterparts in the real sector. As a result, investors anxious to find the next big dot-com were more than willing to overlook fundamental company analysis involving metrics such as price-earnings (P/E) ratio and base confidence on technological advancements.

For example, companies that had yet to generate any revenue, or profits, had no proprietary technology, and, in many instances, no finished product went to market with IPOs (Initial Public Offering) that witnessed their stock prices triple and quadruple in a day, leading to market-wide over-valuation of Internet firms. These outrageous valuations resulted in overwhelming demand, paving the way toward the inevitable burst of the bubble.

The overvalued and highly speculative startups eventually culminated in a stock market surge in 1995. Correspondingly, 1997 saw record amounts of capital flow into the Nasdaq, leading up to 39% of all venture capital investments going to Internet companies by 1999. That year, most of the 457 IPOs were related to Internet companies, followed by 91 in the first quarter of 2000 alone. As a result, between 1995 and 2000, the Nasdaq Composite stock market index rose 400%.

Why did the dot-com bubble burst? 4 main reasons

The eventual crash of the dot-com bubble can be attributed to the following factors:

#1 Absurd overvaluations of dot-coms

One massive contributor to the dot-com bubble was investors’ lack of due diligence. Due to soaring demand and a lack of solid valuation models, most internet companies that held IPOs during the dot-com era were excessively overvalued. In short, companies were valued on earnings and profits that would not occur for several years, assuming that the business model actually worked, and investors were inclined to ignore traditional fundamentals.

As a result, investments in these high-tech companies were highly speculative, without solid profitability indicators rooted in data and logic, such as P/E ratios. Undoubtedly, this shortsighted investing strategy– resulting in unrealistic values that were too optimistic– blinded investors from the warning signs that ultimately signaled the bubble’s rupture.

#2 Lavish spending habits of dot-coms

With venture capitalists throwing money at the sector, dot-coms were racing to get big quickly, often spending a small fortune on marketing to establish brands that would distinguish them from the competition, with some throwing as much as 90% of their budget on advertising.

As a result, most Internet companies incurred net operating losses as they spent lavishly on advertising and promotions to build market share (percentage of a market/industry controlled by the company) or mind share (consumer awareness or popularity surrounding the company) as fast as possible. In addition, frequently, these companies would offer their services or products for free or at a discount to create enough brand awareness to charge profitable rates in the future.

Moreover, tech companies at the time were known for throwing expensive events called dot-com parties to generate buzz upon a launch (or any other reason for celebration, really). Budgets of up to a million dollars a month would sponsor extravagant parties in the Bay area, turning networking events into PR machines.

Indeed, the parties were often not more than pure exuberance facilitated by cheap money, rarely benefitting the company’s bottom line. This mindset was accurately concluded by Declan Fox, director of business development for Sony Music: “No one cares who threw the party, as long as it’s an open bar.”

We recommend you read Ranjan Roy’s article about DoorDash and “pizza arbitrage” as he compellingly demonstrates the failing business models of today’s delivery platforms: A pizza restaurant owner sees that DoorDash is selling his $24 pizzas for only $16, presenting him with an arbitrage (the simultaneous purchase and sale of the same product in different markets to profit from the difference in the listed price) opportunity: Order his pizzas at $16, sell them to DoorDash for $24 each, and pocket the difference.

#3 A surplus of venture capital

Money pouring into dot-coms by venture capitalists and other investors was a primary reason for the bubble. Moreover, cheap money available through very low-interest rates made capital easily accessible. Furthermore, the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 lowered the top marginal capital gains tax in the U.S. and made people even more willing to make speculative investments.

That, coupled with fewer barriers to funding for tech and internet startups, led to massive investment in the sector, expanding the bubble even further.

#4 Encouragement by the media

Media companies encouraged the public to invest in risky tech stocks by peddling overly optimistic expectations of future returns. Similarly, business publications – such as The Wall Street Journal, Forbes, Bloomberg, as well as many investment analysis publications – stimulated demand even further, taking advantage of the public’s desire to invest in the stock market.

The dot-com bubble bursts

The Nasdaq index peaked at 5048 on March 10, 2000, nearly doubling from the previous year. After the peak, several leading high-tech companies, such as Dell and Cisco (NASDAQ: CSCO), placed colossal sell orders, sparking panic selling among investors, resulting in the value of many tech companies nosediving. Within weeks, the stock market had lost 10% of its value.

The downturn was further intensified by:

- Concerns that the Y2K problem might trigger broader social or economic issues: Spending on technology was volatile as worries mounted that computer systems would have trouble changing their clock and calendar systems from 1999 to 2000;

- New heights in marketing spending: Spending on advertising reached new heights for the sector as dot-com companies purchased astronomically costly (30-second commercial was around $2 million) ad spots for the Super Bowl;

- Rising interest rates: The Federal Reserve increased interest rates several times between 1999 and 2000. Higher interest rates curb market enthusiasm and encourage investors to move investments from more speculative assets into safer interest-paying holdings like bonds;

- Recession in Japan in March 2000: News that Japan had entered a recession triggered a global sell-off that disproportionately affected technology stocks, moving even more funds out of speculative assets and into safer, fixed-income instruments like bonds. Soon after, Nasdaq fell 2.6%, but the S&P 500 rose 2.4% as investors shifted from strong-performing technology stocks to poor-performing established stocks;

Ultimately, these factors helped catalyze the bursting of the overinflated Internet bubble. As cash-strapped Internet companies began to lose value, spreading fear among investors and causing additional selling, a self-reinforcing process called capitulation (a mass surrender to the declining market) took hold. As a result, dot-com companies that reached market capitalizations in the hundreds of millions of dollars became worthless within months.

The sell-off continued until the Nasdaq hit its bottom around October 2002, dropping to 1,114, down 78% from its peak. By 2001, a bulk of publicly traded dot-com companies had folded, with trillions (estimated $5 trillion) of dollars of investment capital evaporated.

It took until 2008 for high-tech industries to exceed unemployment levels before the recession, increasing 4% from 2001 to 2008. The tech industry in Silicon Valley took longer to recover, with some companies having to relocate production phases to lower-cost areas.

The companies that crashed but survived the dot-com bubble

After venture capital dried up, so did the start-ups they funded. The lifespan of a dot-com was directly correlated to its burn rate, the rate at which it was burning through its capital—resulting in many dot-com companies going into liquidation. Moreover, supporting industries, such as advertising and shipping, scaled back their operations as demand fell.

Multiple Internet companies and their executives were accused (or convicted) of fraud for misusing shareholders’ money. In addition, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) imposed hefty fines against investment firms, including Citigroup (NYSE: C) and Merrill Lynch, for deceiving investors.

However, a select few– through reorganization, new leadership, and redefined business plans– managed to adapt and thus survive the burst. Some companies that managed to do just that include Amazon (NASDAQ: AMZN), eBay (NASDAQ: EBAY), Priceline, and Shutterfly.

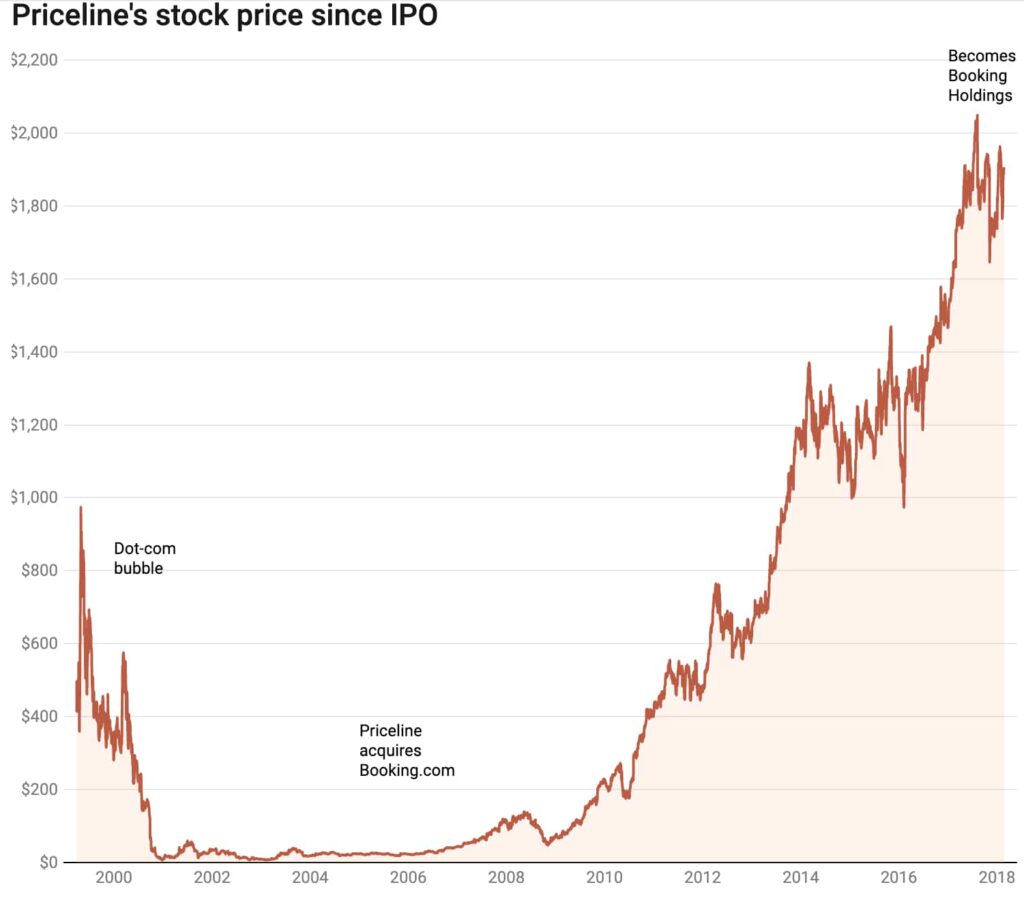

Priceline

The company that most exemplified the dot-com era was Priceline. Launching in 1998, Priceline was founded by Jay Walker and intended to solve the problem of unsold airline seats. Priceline’s fix was to offer these seats to online customers who could name the price they were willing to pay.

As a result, customers got cheaper flights, and airlines sold excess inventory. In short, inefficiencies were ironed out of the market, and Priceline took a cut for streamlining the process.

The company was a dot-com sensation, expanding from 50 employees to more than 300 and selling an excess of 100,000 airline tickets in its first seven months of business. By 1999, it was selling more than 1,000 tickets a day.

Walker wanted to saturate the market by building a brand through rigorous marketing. So the company spent more than $20 million in advertising in its first six months, eventually placing fifth in internet brand awareness by 1998, preceded only by AOL, Yahoo, Netscape, and Amazon.

And so, in March 1999, Priceline went public at $16 a share, eventually settling at $69, giving it a market capitalization of $9.8 billion, the most significant first-day valuation of an internet company to that date.

At the same time, Priceline had racked up losses of $142.5 million in its first few quarters in business. In addition, it bought tickets on the open market to fulfill customers’ bids, thus losing approximately $30 on every ticket it sold. Furthermore, Priceline customers frequently paid more at an auction than they could have through a traditional travel agent.

None of this fazed investors, however, because they were more interested in grabbing a slice of the buzz. It didn’t matter for venture capitalists either, whose goal in backing companies like Priceline, eToys, and Kozmo.com, was outlandish IPOs, since that’s when they got paid.

Best Crypto Exchange for Intermediate Traders and Investors

-

Invest in cryptocurrencies and 3,000+ other assets including stocks and precious metals.

-

0% commission on stocks - buy in bulk or just a fraction from as little as $10. Other fees apply. For more information, visit etoro.com/trading/fees.

-

Copy top-performing traders in real time, automatically.

-

eToro USA is registered with FINRA for securities trading.

Incredibly, by 1999, losing money was a sign of a successful dot-com, and Priceline was the front-runner. Indeed, so many of the companies that would embody the dot-com bubble (e.g., Pets.com, eToys, Kozmo.com, UrbanFetch) shared some or all of Priceline’s qualities:

- A promise to change the world;

- A get-big-fast strategy to gain market domination;

- A propensity to sell products or services at a loss to acquire that market share;

- Lavish spending on branding and advertising to raise brand awareness;

- A monstrous valuation that was detached from profitability or rational metrics.

In the end, the company lost $1.1 billion in 1999, and its stock tanked from $974 to $7 a share. Another blow came with 9/11, with the entire travel industry facing challenges. However, things began to change when Jeff Boyd took over as CEO in 2002, rebuilding the Priceline brand around hotels rather than on airfares and expanding its European market.

Priceline (now under Booking Holdings) currently works with over 100,000 hotels in more than 90 countries and has enjoyed revenue as well as net income growth over the last several years. Booking Holdings (NASDAQ: BKNG) now includes Priceline and former competitor travel sites Kayak, Booking.com, Agoda, Open Table, and RentalCars.com. As of October 2023, its shares trade at around $2,800.

Winners and losers of the dot-com bubble

An asset bubble can be highly damaging, especially for those who arrive late. The average investor who came in with the dot-com buzz and bought at the peak had a genuine risk of losing it all. Venture capitalists, however, were not concerned about a company’s profitability or a bubble brewing. Any IPO meant an exit, a payday.

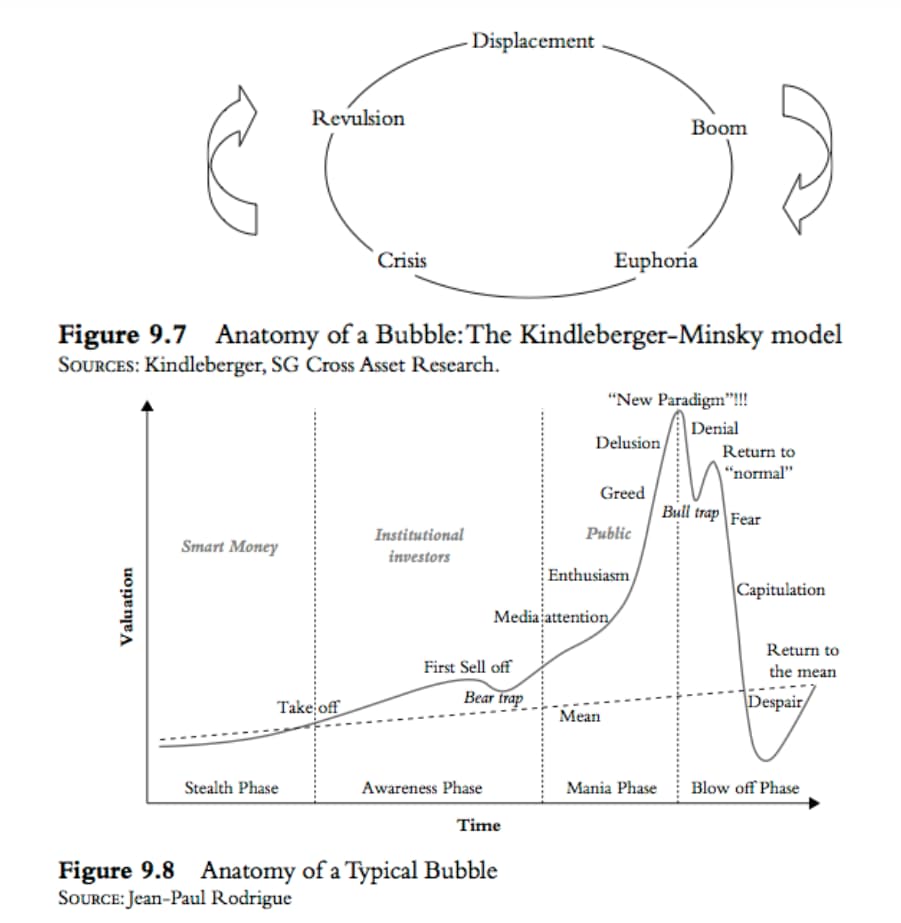

There are five steps in the lifecycle of a bubble: displacement, boom, euphoria, profit-taking/crisis, and panic/revulsion. The graph below demonstrates these five stages, as well as when different types of investors come in, starkly illustrating the collapse’s brunt on latecomers.

Who was most affected by the dot-com bubble collapsing?

Unfortunately, like with most asset bubbles, everyday people (the public) were the most aggressive investors in the dot-com bubble when the bubble was at its peak, and the smart money was getting out. For example, over the year 2000, individual investors continued to pour $260 billion into the stock market as it began its meltdown, a substantial increase from 1998 with $150 billion invested and 1999 with $176 billion invested in the market.

And by 2002, 100 million individual investors had lost a collective $5 trillion in the stock market. In addition, a Vanguard study showed that by the end of 2002, 70% of 401(k)s had lost at least one-fifth of their worth, and 45% had lost more than one-fifth.

Simultaneously, an entire generation of workers who staked their careers on the dream of technology were let go. It’s now estimated that between 2001 and early 2004, Silicon Valley alone lost 200,000 jobs.

Who were the biggest gainers of the do-com bubble?

Naturally, the era didn’t end miserably for everyone. For example, between September 1999 and July 2000, insiders at dot-com companies cashed out $43 billion, twice the rate they’d sold during 1997 and 1998. Moreover, in the month before the Nasdaq peaked, insiders sold 23 times as many shares as they bought.

The most successful trade of the dot-com era

In the mid-1990s, at the dawn of the dot-com bubble, Mark Cuban was pitched by Todd Wagner, a friend, and fellow sports fan, to start an internet audio company where users could listen to sports games online. Sold on the possibilities, Cuban agreed, and in 1995, the duo created AudioNet, which later became Broadcast.com. The company went public in July 1998, its stock price soaring 250% on its first day of trading, a then-record for newly issued public stock.

The company’s success caught the fancy of Yahoo!, who acquired Broadcast.com in 1999 for $5.7 billion in Yahoo! stock. Incredibly, after the sale, Cuban knew to hedge against the risk of a decline in the value of the Yahoo! shares he now owned by shorting Yahoo! stock. A profoundly savvy tactic, now knowing of the crash that ensued.

Unfortunately, all of Yahoo!’s broadcasting services were discontinued only a few years after the acquisition, its expensive purchase widely considered one of the worst Internet acquisitions in history.

Recommended video: Watch the Shark Tank billionaire explain in 1 minute how he escaped the dot-com crash.

Dot-com era legacy

While most tech startups vanished, the capital injected into them during the dot-com crash era laid out the digital infrastructure and economic foundation that would eventually allow the Internet to mature.

Similar to dot-coms, telecommunications companies, too, experienced a bubble that concluded in a tragic crash. But before the bubble burst, telecom companies managed to raise $1.6 trillion on Wall Street and invest more than $500 billion into laying fiber optic cable, adding new switches, and building wireless networks.

The 80 million miles of fiber optic cable represented 76% of the total digital wiring installed in the U.S. up to that point and would allow for the future development of the Internet.

The resulting excess of fiber in the years after the collapse and the severe overcapacity in bandwidth for Internet usage meant that the next wave of businesses could deliver sophisticated new Internet services cheaply. By 2004, bandwidth cost had fallen by more than 90%, despite Internet usage doubling every few years. And as late as 2005, as much as 85% of broadband capacity in the country was still going unused.

So, after thousands of jobs lost and billions of investment dollars down the drain, perhaps we can look at the groundwork that was laid for the future of the Internet as the one saving grace. Venture capitalist Fred Wilson, who himself lost 90% of his net worth in the crash, has described it as such:

“A friend of mine has a great line. He says, ‘Nothing important has ever been built without irrational exuberance. Meaning that you need some of this mania to cause investors to open up their pocketbooks and finance the building of the railroads or the automobile or aerospace industry or whatever. And in this case, much of the capital invested was lost, but also much of it was invested in a very high throughput backbone for the Internet, and lots of software that works, and databases, and server structure. All that stuff has allowed what we have today, which has changed our lives … that’s what all this speculative mania built.”

Dot com crash vs. crypto crash similarities

The cryptocurrency and Bitcoin (BTC) boom, which started around 2019 and lasted through the Covid-19 pandemic until January 2022, has been compared to the dot com boom, where the prices of cryptocurrencies, altcoins, and other digital assets like NFTs spiked in a steeper-than-average bull market, subsequently crashing after highly speculative investments craze.

Recommended video: How the crypto collapse compares to the dotcom bubble

Drawing parallels — layoffs, scandals, and bankruptcies — there are a few things in common. However, coinciding with a looming recession – rising inflation, interest rates, as well as the war in Ukraine and the Covid-19 pandemic aftermath, makes this one a more anticipated occurrence.

Despite, let’s take a look at the similarities:

Speculative investing

One notable similarity is speculation — during the dot com crash, companies benefited from an abundance of venture capital (VC) as well as the retail investor funding without producing a profitable company with a real product or having to prove they were making proper sales.

Just like the tech bubble of the 2000s, the crypto bubble, along with new blockchain technology and DeFi projects, has benefited from speculative investments from people simply believing in the new innovation based on hype and strong belief in the new technology.

New technology

Similarly, in both the dot com era and the cryptocurrency and blockchain technology boom, people kept and keep showing confidence in these companies, believing in the future of the new tech industry innovations and that crypto can still be the future of finance.

Accelerated growth

Even though not quite the same, drawing similarities, both the dot com crash and crypto crash have experienced a similarly accelerated boom-and-bust development. The crypto crash in January 2022 reportedly wiped out 60% of the total value, where the market cap dropped from $2.188 trillion to $860 billion, wiping over $1.3 billion of its value.

IPO vs. ICO

IPO was the talk of the financial world in the late ‘90s early 2000s during the dot com bubble, where companies with no actual product or revenues went public and doubled, tripled, or quadrupled in value.

Alternatively, ICO, or Initial Coin Offering, is the cryptocurrency equivalent of an initial public offering (IPO). During the ICO boom that started in 2017, roughly a whopping 80% or more ended up scams, frauds, or simply unsuccessful — products or services were either not thought through, didn’t have a proper business plan, or had no clear value or target audience. It resulted in stricter regulations – the Howey Test, used by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the US, now used to determine the legality of each project before the ICO.

Dot com bubble vs AI bubble

The dot-com bubble was marked by massive speculation and overvaluation of internet companies, many of which lacked viable business models or profits, leading to a significant market crash when the bubble burst.

While current stock valuations for AI companies are generally lower than those during the dot-com bubble, mega-cap tech stocks, such as Nvidia and Microsoft, are significantly outperforming small-cap stocks at rates not seen since the dot-com bubble. This trend has raised concerns about market concentration and systemic risks within the U.S. economy.

However, the two periods differ in two key aspects:

- AI technologies are already delivering tangible value across various industries, such as healthcare, finance, and automotive, which wasn’t the case with many dot-com companies;

- Many leading AI companies are well-established and profitable, unlike many of the fledgling companies that contributed to the dot-com crash.

Small caps outperform Nasdaq 100 in longest streak since dot-com crash

How to avoid economic bubbles?

Some of the measures investors can take to avoid the formation of an asset bubble include:

- Proper investigation of company metrics: Instead of chasing the buzz, investors should consider investments in startups only after examining financial variables, such as the business’s overall debt, profit margin, dividend payouts, and sales forecasts. It’s essential to evaluate long-term potential, as a short-term focus can lead to the emergence of another economic bubble;

- Avoid speculative investing: Valuations of speculative investments are sometimes overly optimistic. Therefore, investors should refrain from investments based on unrealized potential in companies yet to prove their profitability and long-term sustainability.

- Look for sound business models: Avoid investing in companies that lack a solid business model or ones that boast unrealistic revenue growth prospects;

- Diversification: Spreading your investments out sufficiently will minimize the impact of any one bubble bursting;

- Avoid companies with a high beta coefficient: To evaluate the relationship between the company and the stock market, investors can determine the company’s beta coefficient, which expresses the degree to which the stock moves with the economy. For example, a beta value of 0.5 indicates that the stock increases by half as much whenever the market increases. During the Internet bubble, most startups posted high beta values (greater than 1), i.e., their decline in a market downturn would be much more than the average market fall. A high beta coefficient alerts investors to a high-risk stock during a recession. The opposite applies during a market boom, so investors should be wary of a bubble formation.

In conclusion

To sum up, the dot-com bubble and crash thereafter was caused by the lack of due diligence by investors who, driven by herd mentality and media frenzy, poured money into Internet startups, completely overlooking fundamentals. So, as young investors, if your only motivation to invest in something is FOMO (fear of missing out), take a step back. Instead, to dodge the pull of a bubble, consider factors such as the P/E ratio, intrinsic value, debt-to-equity ratio, dividend payouts, etc.

Disclaimer: The content on this site should not be considered investment advice. Investing is speculative. When investing, your capital is at risk.

FAQs about the dot-com bubble

What was the dot-com bubble?

The dot-com bubble was a stock market bubble triggered by speculation in dot-com or internet-based companies during the bull market from 1995 to 2000. It was an economic bubble that saw the value of equity markets grow dramatically, with the technology-dominated Nasdaq index rising five-fold during that period.

What caused the dot-com bubble?

The dot-com bubble and the dot-com crash thereafter was fueled by a combination of speculative investing, market overconfidence, investors’ fear of missing out, an abundance of venture capital funding, and the failure of Internet startups to turn a profit.

What was the timeline of the dot-com bubble?

The dot-com bubble lasted about two years, from 1998 to 2000. The period from 1995 to 1997 is regarded as the pre-bubble period when things really started to pick up in the tech industry. The crash ultimately saw the Nasdaq index plunge 76.81%, from 5,048.62 on March 10, 2000, to 1,139.90 on October 4, 2002.

What companies survived the dot-com bubble?

Few managed to come out the other side after the dot-com bubble’s spectacular rise and ensuing crash. However, many companies that did survive the dot-com bust did so by ignoring the dominant get-big-fast business mode. Some companies that managed to do just that include Amazon, eBay, Priceline, and Shutterfly.

What is the difference between the dot-com bubble vs now?

The dot-com bubble of the late 1990s and the current startup environment represent two distinct periods in tech investment. The late ’90s saw rampant speculation in internet companies, many of which lacked sustainable business models, leading to the bubble’s burst. In contrast, today’s startups, despite often being unprofitable, typically showcase tangible assets, stronger user growth, and diversified products. Additionally, modern financial regulations provide greater oversight. However, both periods emphasize the danger of high valuations based on future potential rather than current profitability, underscoring the need for investor caution.

Which were some of the notable dot-com bubble companies that failed?

During the dot-com era, numerous companies garnered significant attention due to their rapid valuations. Notable dot-com bubble companies that failed are Pets.com, Webvan, Kozmo.com, and eToys. Many of startups firms had high-profile IPOs but struggled with profitability.

What was the dot-com bubble effect on the economy?

The dot-com bubble had a profound effect on the economy. Initially, it led to massive investments in internet startups, boosting employment and market valuations. However, when the bubble burst, it resulted in significant financial losses, company closures, and a broader economic downturn. The dot-com bubble effect on the economy serves as a reminder of the potential consequences of speculative bubbles.

Did the dot-com bubble ever recover?

The tech sector did recover from the dot-com bubble; by 2017, the S&P 500 Information Technology Index had surpassed its peak from 2000.

Who is to blame for the dot-com bubble?

Many can be blamed for the dot-com bubble, including excessive investment in tech startups without solid profitability indicators, lavish spending by dot-coms to build market share, and a surplus of venture capital fueled by low-interest rates. Moreover, encouragement by the media and a period of excessive hype around internet companies contributed to inflating the bubble. It was a combination of unrealistic investor expectations, easy capital, and speculative business models that eventually led to the bubble’s burst.

How did Amazon survive the dot-com bubble burst?

Amazon survived the dot-com bubble burst by continuing its aggressive growth strategy while simultaneously working to control costs and diversify its business model. Despite facing significant financial losses, Amazon focused on expanding its product lines beyond books and enhancing customer service, which helped retain consumer trust and increase sales. The company’s early investment in technology infrastructure also laid the groundwork for its future success, including the development of its cloud computing services.

What is dot-com bubble and dot-com burst?

The dot-com bubble was a late 1990s period marked by rapid growth and high valuations for internet-based companies, fueled by speculation about the internet’s future. The bubble burst in 2000, leading to plummeting stock prices and many companies going bankrupt, which had significant financial repercussions but also cleared the path for the evolution of resilient tech firms.

What are the differences between the the late 90s dot com bubble vs AI bubble now?

The dot-com bubble was marked by massive speculation and overvaluation of internet companies, leading to a market crash. Lessons learned from this have led to more prudent investment strategies in the AI sector. Additionally, AI has broader and more immediate applications, with current investments backed by real-world utility and profitability. This cautious optimism suggests the AI sector is less likely to experience a similar catastrophic collapse.

Best Crypto Exchange for Intermediate Traders and Investors

-

Invest in cryptocurrencies and 3,000+ other assets including stocks and precious metals.

-

0% commission on stocks - buy in bulk or just a fraction from as little as $10. Other fees apply. For more information, visit etoro.com/trading/fees.

-

Copy top-performing traders in real time, automatically.

-

eToro USA is registered with FINRA for securities trading.